This spring semester started off with a bang–and not in a good way when it comes to preventable injuries like exertional rhabdomyolysis.

Commonly known as “rhabdo,” exertional rhabdomyolysis is a severe muscle tissue injury usually brought on by inappropriate progression to heavy training and it's been making headlines lately for all the wrong reasons. First, we heard that several members of the Concordia University Chicago men's basketball team were injured by a punishment session that media reports said was issued by basketball coaches in response to a road trip curfew violation . Then several members of the Rockwall-Heath High School football team were injured from a workout. Media reports said the football coach (who was apparently not qualified as a strength and conditioning coach) made them do a ton of push ups during a workout. It was implied that the excessive volume of push ups was a strategy intended to drive home the point that the athletes were expected to win a state championship.

Related: 10 Questions About Injury Prevention & More With Athletic Trainer KatieRose Healey

While many other examples exist, perhaps the most high profile event that made national headlines within recent years was at the University of Oregon, where players had to do a bunch of body weight exercises for 3 consecutive days in a misguided team-building exercise that followed a coaching change. Like the above examples, several players got rhabdo as a result of the training sessions, so obviously there was something wrong with the methods used.

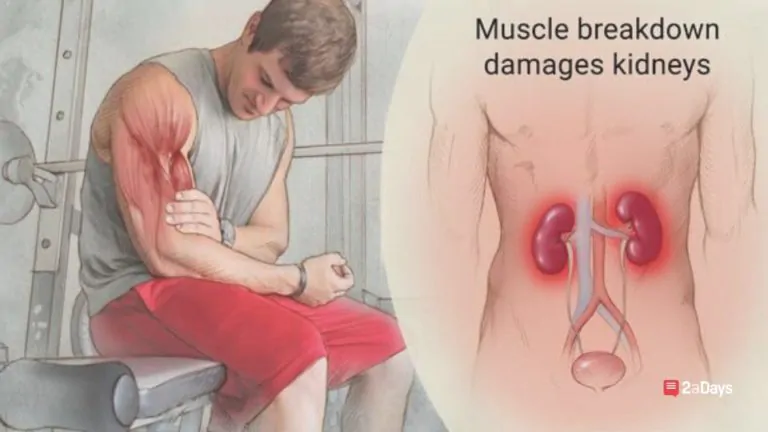

Each year, we seem to hear about another sports team with athletes getting exertional rhabdomyolysis injuries in training and the consequences can be severe: In brief, long term damage to the kidneys and other issues are possible, and a gently progressive, medically-managed return to training that can take weeks or months is often necessary. In athletes, rhabdo is a preventable issue and should be exceedingly rare…but unfortunately, rhabdo seems like it is getting more common. In this article, I'll discuss a few events of concern, some causes of these preventable injuries, and what you can do to protect yourself or your athletic loved ones. The first step to fixing a problem comes with identifying what's wrong…so here we go. First, we can observe two key themes in rhabdo incidents.

Theme #1: Culture of Physical Punishment

Ingrained in team sport, physical punishment is a cultural norm that athletes learn from their own coaches. Make an error? Run a lap. Drop a ball? Do 10 up-downs. This reality was even reflected humorously in a t-shirt made by a cross country runner, stating: “my sport is your sport's punishment.” While the humor in this can be appreciated by all types of athletes, the prevalence of physical punishment in sport isn't funny.

Often coaches are severe in their application of physical punishment, particularly in American football. Some college programs have their athletes get up early in the morning and “roll” for transgressions (e.g., missing class). In this practice, an athlete is typically directed to lie down and roll sideways across the length of the football field and sometimes the athlete repeats this process multiple times, depending on the number of transgressions or the coach in charge. Unsurprisingly, it is common for athletes to vomit as a result of vestibular stress and vertigo that results from rolling. This is designed to be a severe deterrent, and it is severe…but having a policy including this practice doesn't always stop athletes from missing class. And even if it did, would it be worth putting athletes through unnecessary levels of stress and discomfort when they're already pushed to the max?

Related: Tired? 4 Tips To Help You Avoid Overtraining

Many other examples of physical punishment exist, from running stadium steps to other, more creative methods and unfortunately, all physical punishment methods have physiological consequences. Anything presenting substantial stress to an athlete may take days or weeks to overcome, especially if the athlete is under heavy training or in season. Stress is accumulative to the athlete, and coaches must honor that reality. A severe punishment session may not just cause rhabdo, but may also bring about other problems, such as overuse injury, or negatively affect performance in tomorrow's practice or training session due to accumulated fatigue. Doing 80 up-downs today may present the figurative straw that breaks the camel's back, which leads to an injury tomorrow—so it is really important to not overdo punishment.

Like anything in sport, coaches must be critical about our practices so we can adjust our process and policies—this means we reflect on why we're doing what we do, if the practice is appropriate and successful, and what adjustments or alternatives might be needed. After all, most people would agree that good coaching involves awareness of details and deliberate application of methods. This is definitely important if something we are doing is dangerous, degrades the team culture, or fractures the critically important coach-athlete relationship.

In truth, we seldom find examples of coaches who don't use some type of physical punishment. The challenging reality to this topic—and we see this in each event that shows us that our approach isn't working to protect athletes—is that much of punishment in sport often includes elements of hazing, abuse (when excessive), and other issues like athlete rights. School or university policies are often established by student affairs administrators to protect student rights and prevent physical punishment in extracurricular groups (e.g., clubs, fraternities, sororities), but for what seems like cultural reasons, this protection isn't always extended to athletes in sport environments. Sport administrators, leagues, and associations appear to default to coach prerogative on the application of punishment in practices, etc. But should they give clearer guidance? Should coach education and supervision methods establish guardrails for what is accepted and not appropriate?

Alternatives to physical punishment exist!

Various non-physical methods of keeping athletes accountable exist, and some are actually better in the long term than physical punishment. When we look at the Concordia University-Chicago rhabdo event, after he learned the athletes had missed curfew, the coach could've just benched the offending players. If insufficient players were left to field a team for the road games, he could've just brought the team home and forfeited the road games because the players weren't taking them seriously. Either of these alternative approaches sends a crystal-clear cultural message to the team of what the coach's expectations are, and presents zero health risks for the athletes.

How can I protect myself?

If you're a recruit, you can get a good feel for your potential future program by investigating the coaching staff. For the athlete and their family members, a very important recruiting tip is to sniff out what punishment practices a coach does. Ask specific questions: What will happen to me if I miss class? What will happen if I miss practice? Do you have a curfew in camp and for team travel? How flexible are you in your application of rules due to extenuating circumstances? If the culture of the sport organization seems to have unclear definitions of how punishment is applied, or if excessive physical punishment has been applied by the coach(es), then perhaps that is a program to avoid for safety reasons.

A huge red flag is if a coach who has had a rhabdo event occur in their program before denies the significance of the event, deflects blame to athletes, and refuses to legitimately accept responsibility for the event–this suggests they haven't learned their lesson. If you're already an athlete in a program that is experiencing a coaching change, ask the new coach how much of the culture they set usually includes physical punishment, and how severe it can be. A coach who has the reputation for being a heavy-handed disciplinarian often earns that reputation by delivering physical punishment. All coaches seek to firmly establish their own culture after taking the reins of a program—often more severe responses are delivered up front to set the tone for their tenure.

If you're a current athlete affected by coach turnover, ask your new coach detailed questions to explore how much of their punishment strategy is physical, and how much is delivered by other means (e.g., suspension, losing minutes on the court, cleaning the weight room). This specific line of questioning tells you a lot about how deliberate the coach is in constructing their policies and processes, and helps you figure out how well-prepared they are to mentor athletes. Coaches who are heavy-handed disciplinarians tend to have poor emotional intelligence, which erodes culture of the athletic program. For many athletes, this issue fractures the coach-athlete relationship and leads to less connection with the coach over time. Exploring coach tendencies in this way can help inform you of a need to transfer to a different program out of concern for safety and protection of your well-being.

Theme #2: Group Punishment

For some reason cultural coaching knowledge in team sports suggests that when a team member does something they shouldn't, the rest of the team should also be punished. The line of thinking is that all the athletes are affected by one athlete's lapse of judgment or error in a game, and we should punish the whole team in the same way so they'll police themselves or pressure each other to do better. In truth, coaches who rely on this strategy end up punishing more athletes that are doing the right thing than athletes who aren't—and opportunities for positive reinforcement (like publicly acknowledging those who are doing the right thing…which tends to work very well) are missed. Talk about a mixed message! When coaches reach that point, we also must consider that perhaps we'd be more effective just punishing the individual athlete who did something wrong so the others can get on with what they were supposed to be doing.

Punishment should be appropriate…and there are many tools to use. Early on in my college coaching career, I learned to use physical punishment and extreme responses like kicking an athlete out of a training session. Some colleagues helped me understand that extreme responses don't account for social reasons why something might have happened. Most importantly, because coaching begins and ends with relationships, understanding what's going on with someone else is really important. For example: a high school athlete arrives late and is poorly focused during a training session. Many issues could cause this situation—perhaps they didn't eat breakfast because no food was available and they are now hypoglycemic…perhaps there's a family emergency and the athlete is in a state of distress. Good coaches get to know their athletes and strive to do right by them. The same athlete may do better with a private conversation with their coach instead of making their team do voluminous up-downs in a training session.

Related: 6 Questions With Fairfield University Lacrosse Player, Melissa Taggert, on How to Deal with Injury

Or, maybe we don't physically punish at all–perhaps resolving something contributing to a lack of focus is more important than today's training session. If punishment is a “must” for the coach, perhaps they should consider another tool-such as missing some playing time, or requiring the athlete to clean the weight room or pick up trash on campus.

Can we prevent Rhabdo?

Despite the reality that dehydration and several other factors may increase risk, rhabdo is preventable. The major themes in the vast majority of rhabdo events are: 1) application of exercise the athlete isn't accustomed to (usually volume), 2) non-progressive exercise, and 3) insufficient recovery. Humans are very adaptive to training, and we can tolerate a certain high amount of activity, but if high volume is applied through an excessive shock to the system (i.e., lots packed into today's training session), injury can result. This is true for our ligaments and tendons (as we see in overuse injuries) and our musculature.

Because our muscles are damaged to some extent every time we train, we must be careful to plan training intelligently, ensuring today's session is relevant to the sport and a reasonable progression from the last several sessions. In addition, ensuring recovery days (less intense training or rest) is crucial so our tissue can repair. This snapshot at the physiological impact of training highlights the importance of coach education, training, and certification, along with experience delivering training programs—this needs to be accompanied by guardrails clearly stating what is inappropriate within the sport context (provided by schools and sport leagues/conferences, informed by research). Other specialties such as sport psychology also have important input to guardrails and establishing common practice. If we put under-skilled coaches in charge of designing and delivering training, it can be dangerous.

If high-volume exercise is applied through punishment, there is a very strong likelihood that the coach is committing physical abuse. Athlete maltreatment researchers Ashley Stirling and Gretchen Kerr included “forced physical exertion beyond the physical capabilities of the athlete” and requiring athletes to perform “beyond reasonable training demands” as physical abuse in sport. If the athlete incurs injury requiring hospitalization, the event was clearly beyond their physical capability to recover from. Further discussion and clarification on this issue is apparently necessary from sport researchers and administrators, but it is administrators who will need to establish rules to support athlete safety much better than we're doing now.

Today's athletic administrators, coaches, parents, and other stakeholders should strive to produce an environment for athletes that is safe and supportive. Because rhabdo-producing events tend to involve similar themes, athletic administrators may establish rules for coaches to follow that prevents physical punishment—or at a minimum prohibits reckless and severe punishment—and supports use of other means of punishment that serves the athlete's best interest and long-term development.

Because the value of mandatory coach education programs is not realized by most sport leagues and administrators, these issues will continue because coaches absorb most of their knowledge from cultural norms. Today's athletes and parents must navigate the recruiting landscape carefully to ensure their athlete isn't placed in a situation that may produce preventable injuries like rhabdo. Avoiding a sport organization that supports a culture of punishment and coaches who predominantly use group punishment may be key strategies in supporting athlete welfare.

Have an idea for a story or a question you need answered? Want to set up an interview with us? Email us at [email protected]

Image Credit: MyBurbank

* Originally published on March 6, 2023, by Ben Gleason